Developing Emotional Literacy Across the Grade Levels

Teaching students how to identify and express their own emotions—and consider those of others—empowers them and sets them up for learning.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.When kids learn to use language and self-regulation skills to say things like “I don’t like it when you push me; will you please stop,” instead of responding with a swift shove, there’s an immediate impact: The other child receives clear feedback on their actions, and the incident can turn into a “relationship-building moment instead of a tension moment,” says Antonia Celius, a teacher at Educare New Orleans Early Childhood School.

And when older kids get a few minutes at the beginning of class to settle in with a quick mindfulness exercise, to practice seeing through the eyes of their peers, or to share something they’re grateful for, “it ups the base happiness level for everyone,” says former high school teacher Ronen Habib, and establishes “emotional resonance in the classroom—when brains are in sync in a positive way because people are experiencing positive emotions together.”

Emotions “aren’t good or bad,” says school leader and author Kathryn Fishman-Weaver in her article “Fostering Emotional Literacy Begins With the Brain.” They are biological information. Emotional literacy—the ability to understand, talk about, and eventually manage the biological information supplied by our emotions, and to empathize with other people’s emotions and feelings—involves a sophisticated set of learned social and emotional skills that tend to receive a lot of emphasis in the early grades.

But it’s work that teachers say pays dividends as students progress through elementary school and into the high-pressure environments of middle and high school: “If I do what I’m supposed to do when they are transitioning from early childhood to kindergarten, then when they’re in second grade, they’ll be able to use these skills,” says Celius. “And they can share them with their classmates in third and fourth grade. You won’t have the disruption. You can just teach.” At the same time, the end of elementary school shouldn’t signal the completion of this work: It’s important to continue carving out time to deliver developmentally appropriate activities in the middle and high school grades when teenagers still need lots of support.

Here are practices to help kids at different grade levels develop the vocabulary and practice the emotional literacy skills to better understand and more effectively participate in the world around them.

Build Feelings Vocabulary Early

In the early grades, “children should be able to recognize and accurately label these feelings: sad, mad, happy, afraid, surprised, upset, worried, and proud,” writes Maurice Elias, a professor of psychology at Rutgers University. Consider using flash cards, he says, or picture books—there are plenty that are specifically focused on emotions, but picture and chapter books about other topics often incorporate a broad range of emotions (and accompanying facial expressions), providing rich fodder for conversations. With young students, “first ask about the feelings they see in the images,” Elias suggests. “If they’re correct, ask them how they know. Whether they’re correct or not, point out the variety of ways feelings are shown—different aspects of faces (eyes, eyebrows, mouth, forehead) and postures.”

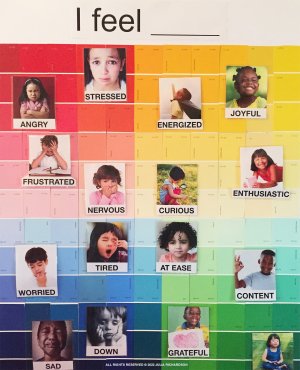

To help students learn the vocabulary to identify and express their feelings, teacher Julia Richardson designed a color-coded feelings chart for her first-grade class, adapting the idea from the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence’s Mood Meter app, a tool for identifying and sorting emotions. A few days after introducing the chart to her students, “they went from saying they felt ‘good’ or ‘tired’ to saying they felt ‘energized,’ ‘down,’ ‘serene,’ or ‘joyful,’” she writes. “We talked about what the words meant, and my students worked together in groups to sort photos of children’s facial expressions into the color zones.”

Create Opportunities for Emotional Expression

Richardson supplemented the feelings chart discussions and group work with quick check-ins at morning circles. “I began inviting students to share how they felt and why, if they were comfortable,” she writes. Devoting time to the topic of students’ feelings sent the message that students’ emotions were “valid and welcome in the classroom and that their emotional well-being is important.”

Or try a quick rose and thorn check-in where kids share a rose—something positive happening for a student that day—and thorns, which are less than positive, or even negative. Make it clear that students can “choose their level of vulnerability,” says community college teacher Alex Shevrin Venet. “Rose and thorn check-ins are opportunities for students to practice being emotionally vulnerable with their peers. This comfort level translates directly into the ability to share opinions and take academic risks in other contexts.”

At the high school level, a quick daily ritual can help recenter kids and foster a sense of community. In Henry Seton’s high school humanities classroom, a different student each day delivers what he calls a “daily dedication,” a 30- to 60-second presentation about anyone they choose—living or dead, real or fictional—who provides inspiration. “It takes less than five minutes total each week, but it’s a prized moment in the day, one that refocuses us, fosters community, and reignites our motivation,” Seton writes.

Teach Kids How to ‘Shift How They Feel’

Once Richardson’s students felt comfortable identifying and expressing their emotions, she introduced strategies they could draw on to positively shift their feelings in various situations: asking an adult for help, for example, or taking a break in a dedicated quiet space, and using words during a conflict. “Gradually, I noticed this vocabulary showing up in students’ conversations and collaboration,” Richardson writes. “Arguments didn’t solely end in students just walking away; with some support, they could talk it out and keep working together in class.”

When teachers give students space to quiet down and reflect on where they’re at, it’s a concrete way for them to practice emotional intelligence skills such as self-awareness and self-management, says high school teacher Aukeem Ballard. “The hypothesis is that if you can do that, then you are better equipped to interact with your environment in a proactive way, instead of in an extremely reactive way,” says Ballard, who incorporates a mindfulness exercise in his classroom once a week. During the exercise, students stand in a circle, focus on their breathing, and then turn their attention to reflection. “Sometimes we reflect on the theme we’re going to discuss in class,” Ballard notes. “I always spend a minute having everyone, including myself, focus on how we’re showing up in the space. We always make sure to validate how we are showing up without judgment toward ourselves.” The benefits of the exercise—reduced stress, boosted working memory, and lowered emotional reactivity—make the practice “no longer a nice-to-have, but rather a necessity,” Ballard says.

Practice Taking Other Perspectives

Our brains are constantly working to infer the intentions, emotions, and beliefs of others—something psychologists refer to as —so that we can respond appropriately in various social interactions. For most kids, that’s complex work, and misunderstandings pop up often, even for the most socially astute. Theory of mind research holds that our ability to predict how other people will behave is a developmental ability: “Children—from early years through middle childhood, and adolescence to adulthood—change and develop their understanding of self and others, as well as ambiguous situations and emotions and sarcasm,” note the authors of a . Families, peers, and schools in particular, they add, can exert significant influence on this development.

Exercises that allow kids to think through what other people may be experiencing or feeling, to inhabit the inner worlds of others in order to develop understanding—during read-alouds or independent reading, asking kids to “flip the story” for a moment and tell it through the eyes of another character, for example—can be productive. Or try a reflective listening activity: After several months of developing emotional vocabulary, students in Richardson’s classroom paired up and, drawing from a visual anchor chart, “took turns expressing how they felt, mirroring their partner’s language, and recalling a time when they felt similarly,” she writes.

To help her students learn about each other’s identities, and understand their own biases and prejudices, middle school educator Shana V. White has her students create identity portraits. First they draw their own head and shoulders, then a line down the middle of their face. Then they color one side, “like the skin tone, the jacket or shirt that they’re wearing,” says White. On the other side, “I want them to add in their identity markers. And kids kind of tell their own story. They tell me who they are through a picture.” Focusing on visible and invisible identity markers like mental health or sexual orientation, White leads a discussion about perceptions of people, bias, and prejudice. “It’s a really big growth point for a lot of kids, that they are able to be comfortable with who they are, and recognize and respect the identity markers of anybody.”